Otis Taylor is fun to write about because he’s so unique. He’s always changing his game. He doesn’t fit any of the stereotypes we associate with blues. It’s impossible to grade him on the authenticity scale, because it’s irrelevant to his sound, and it doesn’t matter anyway because if you like blues, you’re going to love Otis. He’s African American, but that defines him about as accurately as it did Jimi Hendrix. In other words he transcends all the boxes journalists and record company A&R guys like to stick on musicians.

Otis Taylor is fun to write about because he’s so unique. He’s always changing his game. He doesn’t fit any of the stereotypes we associate with blues. It’s impossible to grade him on the authenticity scale, because it’s irrelevant to his sound, and it doesn’t matter anyway because if you like blues, you’re going to love Otis. He’s African American, but that defines him about as accurately as it did Jimi Hendrix. In other words he transcends all the boxes journalists and record company A&R guys like to stick on musicians.

Not only is he unique, but he’s a character to boot. A couple of examples: he used to ride to high school in Boulder, Colorado, on a unicycle playing a banjo. His wife, a librarian, told him his first album would be his last. Fifteen albums in, she’s still telling him that. After all, when she married him he was an antique dealer. He calls his music trance blues, but its psychedelic strains owe nothing to drugs because he’s never taken any even though his mother was a heroin dealer.

Guitar Player magazine has labelled him the hardest interview they ever did. He’s great on small talk, but sometimes he treats serious questions as if you’d just asked him his favorite color. I booked him for a gig with my blues society in 1999 after When Negroes Walked The Earth came out. He drew about 45 people, but nearly all of them bought the album.

When I called this time for our scheduled interview, he asked if I could call him back because he was in the bathroom. I did and we spent 10 minutes talking about everything from Donald Trump to silverware which he says is the best antique value in the current market. Finally he asked, “Anyway, you want to ask me something,” and we were off.

Hey Joe Opus Red Meat was my favorite album of 2015. On it Otis takes the ’60s, chestnut “Hey, Joe,” vamps on it with such sophisticated arrangements, you have to keep reminding yourself that this isn’t Miles Davis slumming in psychedelia. “This is the hardest album I ever did,” he reveals.

How cum?

“Because I had to work from both ends into the middle ’cause it’s an opus. It continues. Did you listen to the whole thing all in one sitting? It just keeps on going. If you don’t look at the whole thing and just close your eyes, you don’t know where you are sometimes.”

Did he jam the whole thing at once?

“No, but I had to work on it. It was hard. Wasn’t easy. Releases were hard. Everything was hard. I had to just figure it out. I tried to do something different. I always do “Hey, Joe” live, so what the hell? Why not do it? It’s the only cover I do. So, I thought you know, I just try to think of something different, but I lost my record company (Telarc) over it because they weren’t too excited about it.”

Turns out Otis liked Love’s version of “Hey, Joe” better than Hendrix’s. “When I was a kid, I was upset that Hendrix did it so slow. I didn’t understand it. That’s like this is really slow. Then I got into it later, you know.”

Turns out Otis liked Love’s version of “Hey, Joe” better than Hendrix’s. “When I was a kid, I was upset that Hendrix did it so slow. I didn’t understand it. That’s like this is really slow. Then I got into it later, you know.”

Love was a mid-60s pop rock band led by a charismatic British singer Arthur Lee. “In ’64 or ’65 I wanted to be a mod just like Arthur Lee because the band had two black guys and two white guys. I thought that was really cool because you didn’t have that many black rockers. That was really rare. I was so into Love. I was a kid, still a teenager, you know. I liked pop stuff. I liked folk music. I liked all kinds of music. I wasn’t just a folk blues guy. I liked old timey. I wasn’t so much into jazz, but I liked soul music. I like pop music, certain pop music. I wasn’t a big Beatles guy. I was more Stones.”

Our interview took place just after six days in the studio recording his next album. He was in the mood to talk process which is really private territory for a man who may be one of the most outré musicians since the Haight Ashbury cats changed the definition of rock in the 60s.

“There are two types of people who listen to records: the ones who are very technical like the engineers, the guys who work in the studio, or the audiophile guys that super listen for everything. Then, there’s people that just hear the emotion of the song. I make songs for the emotion of the songs, not too much for the audiophile. I don’t make records for other engineers or other producers. I go for the emotion. So, if there’s a mistake, I’d rather keep the emotion than sacrifice being perfect. It’s just a style.”

Most of the musicians were recorded live on Hey, Joe except for guitarist Warren Haynes.“We sent him the tapes. Warren was the only one not in the studio with me.I did that with the last two albums. I had Gary Moore play on the first one. I had Gary Moore in the studio in England because I didn’t know him too well. After that, I’d just send him the tapes. So, I just sent Warren the tapes. They’re incredible musicians. They know what you want. I give everybody – every lead guitar player to play what he likes, what he feels.

“You would have thought he was in the studio with us the way he played with Ron Miles who was in the studio. Everyone was there except Warren Haynes.He was blending with Ron Miles, the cornet player. So, you know, I thought he would go crazy, but he took a different look at it, but he was cool. What he did was like very subtle, very beautiful, you know. He gave me more textures in the album. You just tell stories and let the listener decide.”

Otis has been quoted saying, “Nobody records like me, so I don’t want to divulge anything, but it doesn’t sound like a song until I put all the parts together. I do the arrangements, but there’s always input from others. It’s always done in the moment. That’s why my records have a live feel.”

He confirmed that in our interview. “That’s’ true. That’s still the same. It’s like building a clay model. You get excited when you put all the parts together. I like playing in the studio the best in some ways ’cause I can control it, but a live concert if your amp blows up you’re f***ed. You have no control. A studio you can really control what you’re doing. Things come to me like dreams in the studio. It’s easy. I just hear things that other people don’t hear. It’s just really cool. It’s just a gift that I have. It’s just weird. And I haven’t lost it yet.

He confirmed that in our interview. “That’s’ true. That’s still the same. It’s like building a clay model. You get excited when you put all the parts together. I like playing in the studio the best in some ways ’cause I can control it, but a live concert if your amp blows up you’re f***ed. You have no control. A studio you can really control what you’re doing. Things come to me like dreams in the studio. It’s easy. I just hear things that other people don’t hear. It’s just really cool. It’s just a gift that I have. It’s just weird. And I haven’t lost it yet.

“I think I’m excited about the new album. I’ve just got to listen to it more. It’s not completely finished, and Todd, my bass player, he’s really excited about it, and I’m always worried about trying to go to like a new form.”

I remind him that he does just that every time.

“I know, but every time it gets harder. I kind of went into the studio with one idea, and I kinda went in a different direction and saw I’m very nervous about it because I had a couple of songs, we were messing around. I go, “God, this is cool.” This is what I was doing. I kinda switched directions somewhat from what I was gonna do. So now I have to figure it out.”

Otis takes on some hot racial issues, and some of his material approaches Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” in terms of taking one’s breath away, but he never passes judgment.

“Because I don’t want to be a hypocrate. I’m not a protest singer. I’m a story teller. I don’t want to be hypocritical. The tribes in Africa would kill each other, take their land and then they’d go and sell their prisoners to the Arab slave traders. The Arab slave traders would sell them to the Europeans. The Europeans would take them over and sell them to the people in America. So there’s still slavery in Indonesia.

“We just don’t know about it ’cause they keep indentured slaves, whatever. They have ways of enslaving people without saying you’re slaves. So, I just say there’s no clean dollars. I just don’t want to get too high and mighty. I always tell people I want to make enough money to have a Porsche. But now it’s an Audi. Audis are one of the sponsors of my festivals. So we have to say Audi. Can’t say Porsche anymore.”

When Otis first learned to play the banjo he was unaware the instrument originated in Africa. “I was scared that I was playing banjo. My banjo teacher had just passed away. I got to play at a party with this bluegrass band called the Dillards, and the guy I was playing in front of said, ‘Hey, you’re a really good picker. You could win one of those contests and go down south.’ I go, ‘Down where?’ It’s like late ’64, ’65. Kill me. I said, ‘I’d be dead. I didn’t want to play this f***ing music. It would kill me,’ and I stopped.

“My idol has always been Charlie Pride. He did more inroads in racism and never got any credit for it. Crossed more bridges and never got any credit. And those were hard bridges to cross. Charlie Pride was a phenomenon. People just didn’t realize it.”

Born in Chicago in 1948, Otis moved with his family to Denver after his uncle was shot to death. His father hung out with jazz people, smoked pot and was “a real bebopper.” His mom was “tough as nails.” Otis calls himself “the black sheep of the family.” Straight as an arrow, he hung out the Denver Folklore Center playing banjo and listening to Mississippi John Hurt.

“I was straight, but I was hanging out with all the hippies and beatniks. I wasn’t doing drugs. My parents smoked pot. My father hung out with jazz musicians. It was subterranean. I just lived a different lifestyle, more like beboppers. You know what I mean?”

“I was straight, but I was hanging out with all the hippies and beatniks. I wasn’t doing drugs. My parents smoked pot. My father hung out with jazz musicians. It was subterranean. I just lived a different lifestyle, more like beboppers. You know what I mean?”

He has no idea if his “trance music” enhances a high. “I can’t tell ya if it does or not ’cause I don’t do drugs. So I really don’t know, but I know you don’t need that to get into a trance. You’ve seen my music. There’s people that listen to songs as we play em. That’s what jazz is. It’s repetition. Voodoo music is the ultimate trance music, and there’s no chord changes in drums. Voodoo, voodoo. That’s Haitian music. That’s just drums. Know what I’m saying? It’s all repetition.”

Otis rushed into the studio in 2010 record Clovis People Vol. 3 (Three is no Volume 1 or 2) after he was diagnosed with cancer, not knowing if he would survive his operation. “I had a heart attack, too, you know.I had a heart attack eight days before I went on the Blues Cruise. I had a stint put in my heart.”

Did it change his approach to creating music?

“I was in a lot of pain. So that was one problem You know, pain has no memory, so I don’t have the same memory as I had at the time. It’s like I’m not having that pain right now, so I don’t really relate to it. It’s like I just said, “F***, this could be my last songs I ever write or sing.”

So, if Otis gives some one-word answers to journalist questions, perhaps it’s just who he is. “What’s wrong with one word? I’m not a man with a lot of words in my songs. It’s funny, people say I write about very uncommercial, very edgy things, and then they want to edit me like Mary Poppins. Listen to my f***ing music. I’m not trying to depress anybody. I’m just trying to make interesting music.

Otis lives in many worlds, and he’s comfortable in all of them. His first professional musical work was with Tommy Bolen of the rock group T Rex. He became an antiques dealer after a proposed deal with the British blues recording company Blue Horizon fell through. His daughter Cassie, herself a blues musician, is now married, has a baby and is living in Kansas. But Otis’ body of blues recordings is impressive and his live concerts are always transcendent .

“People work hard for their money. We try to entertain people. I’m like the Sammy Davis Jr. of the blues. My idols in performing are two people, the Pointer Sisters and then Buddy Guy. They’re great performers – then James Brown. They dare to entertain people. I come from a history of black people who get on stage and entertain people. So, I’m very conscious of entertaining people when I get on stage.”

Visit Otis’ website at www.otistaylor.com

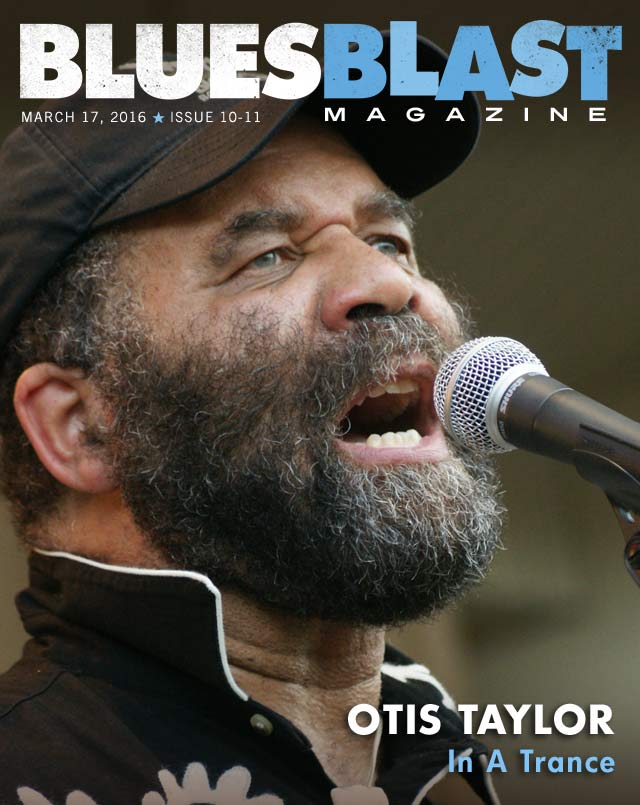

Photos by Bob Kieser © 2016